- All Artworks

- Paintings

- Still Life

Still Life Paintings For Sale

Browse art and see similar matches

Try Visual Search

Category

Filter (1)

Filter

Category

Style

Subject

Medium

Material

Price

Size

Orientation

Color

Artist Country

Featured Artist

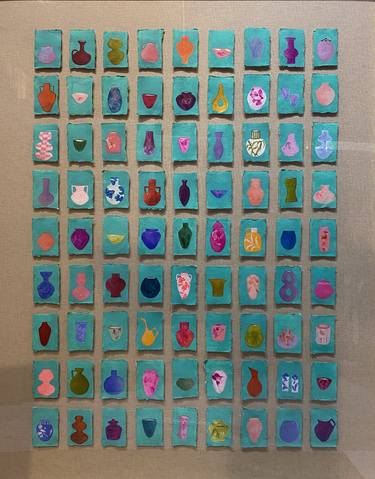

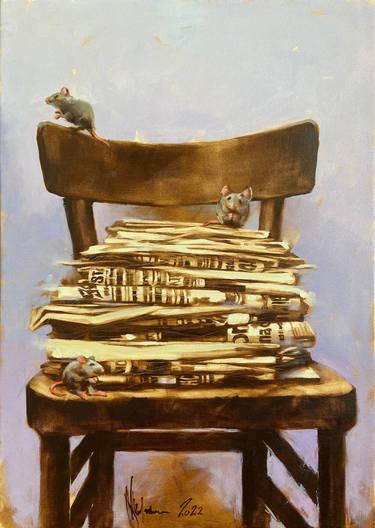

Paintings, 15.7 W x 23.6 H x 0.8 D in

Argentina

$870

Prints from $40

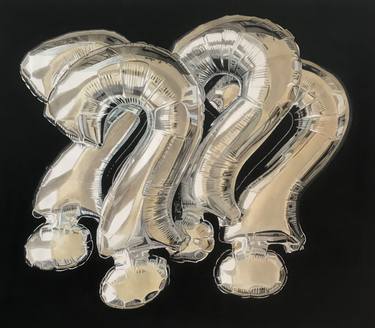

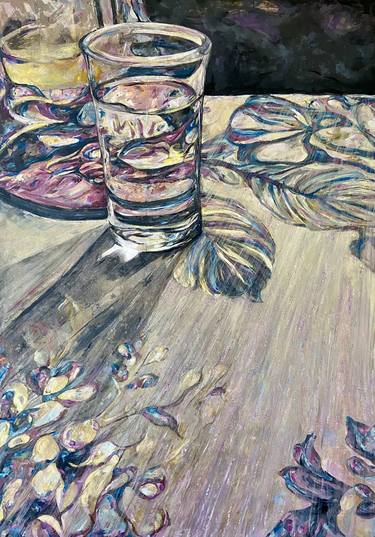

Paintings, 12.6 W x 15.7 H x 0.5 D in

United Kingdom

$1,350

Prints from $40

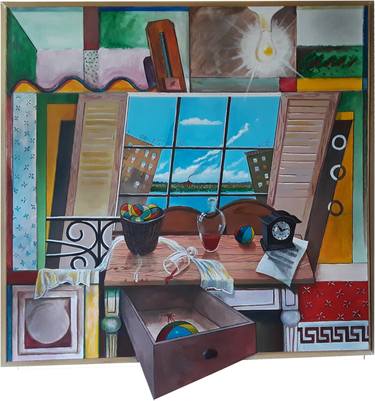

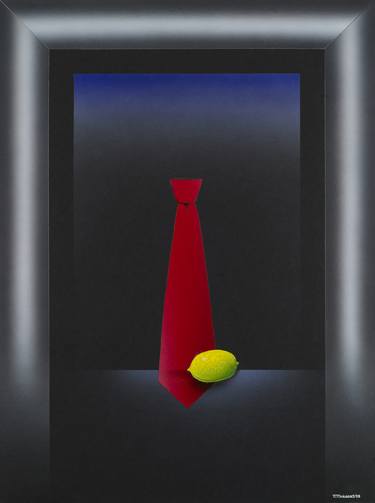

Paintings, 16 W x 20 H x 2 D in

United States

$2,890

Prints from $100

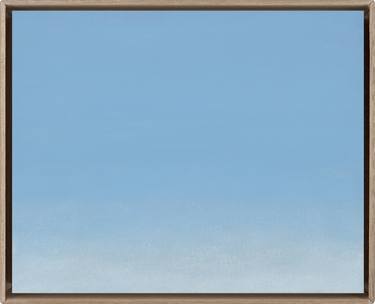

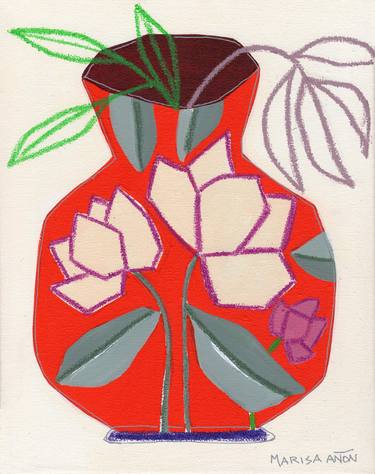

Paintings, 40.6 W x 40.6 H x 2.4 D in

Australia

$4,590

Still life with Pumpkins Original oil Painting

Paintings, 42 W x 22 H x 0.5 D in

United States

$1,127

Paintings, 27.6 W x 27.6 H x 0.8 D in

Hungary

$1,230

Prints from $100

Paintings, 47.2 W x 19.7 H x 0.1 D in

Saint Martin

$1,610

Prints from $100

Paintings, 37 W x 48.8 H x 1.2 D in

United Kingdom

$3,530

Paintings, 34.6 W x 31.5 H x 0.8 D in

France

$2,940

Prints from $40

Paintings, 54 W x 24 H x 1.5 D in

United States

$3,550

Paintings, 24 W x 24 H x 1 D in

United States

$1,800

Prints from $100

Paintings, 52 W x 52 H x 2 D in

United States

$9,660

Paintings, 23.6 W x 23.6 H x 0.8 D in

United Kingdom

$2,190

Prints from $51

Paintings, 24 W x 18 H x 0.1 D in

United States

$1,290

Prints from $70

Paintings, 11 W x 9 H x 1 D in

Netherlands

$1,070

Paintings, 27.6 W x 31.5 H x 0.8 D in

Poland

$3,320

Paintings, 15.7 W x 11.8 H x 1.4 D in

United Kingdom

$1,090

Prints from $99

Paintings, 22 W x 28 H x 0.7 D in

United States

$1,650

Prints from $40

Paintings, 18 W x 24 H x 0.1 D in

United States

$390

Paintings, 35.4 W x 45.3 H x 0.8 D in

Spain

$3,890

Prints from $74

Paintings, 8 W x 9 H x 1 D in

Netherlands

$1,070

Modern abstract art still life 2

Paintings, 48 W x 48 H x 1 D in

United States

$4,195

Prints from $40

Paintings, 11 W x 14 H x 0.1 D in

United States

$510

Prints from $100

Paintings, 23.6 W x 19.7 H x 1 D in

Vietnam

$1,610

Paintings, 19.6 W x 27.4 H x 2 D in

Czech Republic

$1,850

Prints from $190

Paintings, 31.5 W x 23.6 H x 1 D in

Poland

$2,230

Prints from $49

Paintings, 24 W x 24 H x 1 D in

United States

$1,800

Prints from $100

Paintings, 36 W x 40 H x 1.5 D in

United States

$6,670

Paintings, 30 W x 24 H x 0.7 D in

United States

$2,320

Paintings, 12 W x 9 H x 0.8 D in

United States

$195

Paintings, 48 W x 36 H x 1.5 D in

United States

$8,110

Prints from $74

Paintings, 13.8 W x 19.7 H x 0.6 D in

Czech Republic

$2,160

Memento OMI - Nostalgic Offering to the God of Small Things

Paintings, 59.1 W x 29.5 H x 0.2 D in

France

$995

Paintings, 24 W x 24 H x 1.6 D in

United Kingdom

$693

Prints from $100

Paintings, 11.8 W x 11.8 H x 0.8 D in

New Zealand

$1,190

Prints from $40

Paintings, 47.2 W x 47.2 H x 1.6 D in

United Kingdom

$4,900

Paintings, 20 W x 16 H x 1.5 D in

United States

$980

Prints from $70

Paintings, 16 W x 12 H x 0.1 D in

United States

$660

Prints from $70

Paintings, 27.6 W x 39.4 H x 0.8 D in

United Kingdom

$3,480

Contrast of... Senses - 1008 - Limited Edition

Paintings, 23.6 W x 31.5 H x 0.4 D in

Greece

$6,930

Prints from $100

Paintings, 11.8 W x 15.7 H x 0.1 D in

Spain

$415

Paintings, 16 W x 12 H x 0.5 D in

United States

$660

Prints from $70

Paintings, 36 W x 36 H x 1.5 D in

United States

$6,360

Prints from $100

Paintings, 11.8 W x 15.7 H x 0.1 D in

Spain

$415

Paintings, 36 W x 30 H x 1.5 D in

United States

$1,915

Prints from $74

Paintings, 12 W x 9 H x 0.2 D in

United States

$480

Prints from $70

Paintings, 35.4 W x 47.2 H x 0.8 D in

Hungary

$1,270

Prints from $55

Paintings, 24 W x 18.7 H x 0.2 D in

United States

$1,290

Prints from $74

Paintings, 9.4 W x 11.8 H x 0.6 D in

Spain

$310

Paintings, 39.4 W x 27.6 H x 1.6 D in

United Kingdom

$5,440